Everyone is talking about “The Line.” The first truly modern, 21st-century city designed to use ecological technology. A vertical city with housing for millions. A great new model for what cities look like in the future. Or is it?

Recent announcements about the development of The Line have raised questions not only about its viability and scale but also about the soul that’s driving it. Beyond the flashy brochures and the ambitious plans, is The Line on course to become the early 21st century’s biggest engineering folly?

Throughout human history, cities have been staging posts, military garrisons, and the simplest ways of putting the highest number of people into an area. They’ve often depended on a ruler’s determination that a city should exist, what it should look like, and how it should function. That’s because cities are enormous enterprises. They take phenomenal amounts of money and energy to create. How does The Line fit into this historic pattern?

If you’re looking for wealth, will, and governmental power in the 21st century, you could do worse than look at Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. He’s widely regarded as the prime mover behind The Line, able to not only motivate areas of the wealthy Saudi government to commit to the project but also to draw investment from around the world into a bold new city concept. The Crown Prince has been a vital factor in the vision for The Line since it was announced in January 2021.

We’ve said that cities exist for a variety of reasons. So what ultimately is The Line for? First and foremost, it’s part of a larger development, Neom, on the Red Sea, that’s designed to give Saudi Arabia a new and profitable destiny in the potentially post-oil 21st century. To do that, The Line was supposed to be a test case for modern technologies.

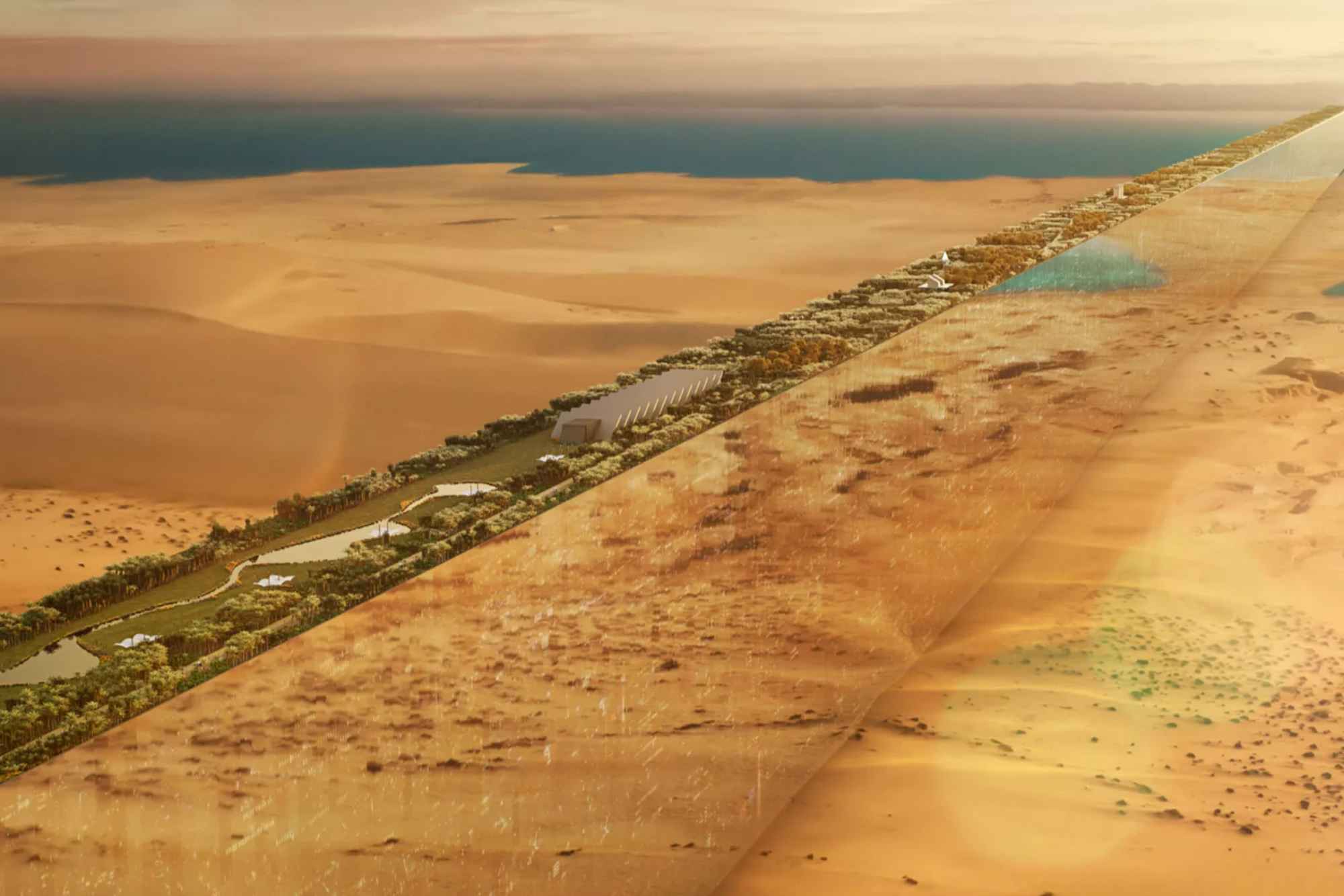

Firstly, it was envisioned as a linear city over 105 miles (170km) comprised of two structures each 500ft tall and 200ft wide, taller than the Empire State Building, with a gap in between. The whole was to be encased in mirrored glass walls. Secondly, it was planned as the most ecologically friendly city in the world. It would have no cars and so no carbon emissions. But your maximum commute time within The Line would be 20 minutes by high-speed rail. Because The Line would be an encased city, communities would be planned on an easy grid. You would never be more than five minutes away from all the amenities you need. No more urban sprawl and grid patterns, just effective community provision. Initial reports boasted that 95% of the land space would be given over to nature, which would be a new way of doing cities. And The Line would be home to 9 million people. That’s just a shade more than live in New York. But it would fit them into a footprint of just 21mi². And this literal shining city would run on 100% renewable energy.

The Line would be humanity’s first attempt to turn science fiction utopia into everyday reality while testing out modern, cutting-edge technologies: minimum footprint, engineered architecture, 100% renewable energy, reliable zero-carbon transportation, and mass habitation in lush, green, community-centered environments. So far, so good. So what could possibly go wrong?

For a while, very little. The Line excited international investment. And as recently as February 2024, earthmovers were working around the clock, shifting millions of cubic meters of earth and water a week to build the footings. Because The Line had some ambitious plans with tight deadlines, the Saudi government hoped to have the first 1.5 million people living in it by 2030.

But the danger in spinning castles in the air is that they depend on ever-forward motion, ever-more investment, and no one asking awkward questions. Introduce doubts or questions, and the entire project can shatter and fall. The first signs that all was not well on The Line came with a radical downshift announcement. The government’s original plan for The Line to house 1.5 million people by 2030 was cut to just 300,000 people by the same point. That was followed up by a huge truncation of the scale of the initial phase. The whole point of The Line was that it was a whole thriving city, 105 miles long. With the announcement of the downshift in population numbers came the sucker punch: 104 of those miles would now no longer be built. In the first instance, just 1.5 miles of habitable line space became the immediate goal.

Suddenly, investors were being asked to pour hard cash not into a groundbreaking 100-mile experiment, but into little more than a vertical village. That’s important because the returns are relatively minuscule, and the truncation makes The Line look more like a Ponzi scheme than the next big thing in techno-assisted living.

But the news got worse. Civil engineers took a look at some of the overblown claims. The whole maximum commute of 20 minutes assertion in particular came under scrutiny. Rafael Pietro Curiel and Daniel Condor published a paper in nature.com, breaking down the problematic math of population density that also championed the idea of building a line-style city. But as a circle. Working on The Line’s initial 105 miles of city and 9 million inhabitants, they worked out that homogenous distribution would give 53,000 people per kilometer. That means if you pick two random people, they’ll be on average 57km apart. The long and short of which means The Line is the longest possible distance between two people. In the original plan, only 1.2% of the population would be a walkable one kilometer away from others. An introvert’s paradise, maybe, but also a mobility nightmare waiting to happen.

If you take those figures and apply them to the engineering of the high-speed rail system, the problem becomes apparent. The Line would need at least 86 train stations to guarantee that everyone is within walking distance of a station. But that means a lot of stops and too short a distance to achieve peak speed between them. Your 20-minute commute just tripled to, on average, at least 60 minutes, and that’s with just 86 stations. That number would include an average walk of 1.3km, which is more than the comfortable optimum people were promised. In essence, the paper proved that while the theory was sweet, the engineering meant that the fundamental backbone of living in The Line simply didn’t work.

For now, the jury’s still out on The Line. As investors wobbled, Saudi Arabia began to offer opportunities to China, both in investment and the actual construction process. In offering solutions to the failed mathematics of the transport system, Rafael Pietro Curiel and Daniel Condor suggested a fundamental form change. Many of The Line’s engineering issues, they said, were rooted in its linear form. If instead, you built the 21st century’s first green-centered city as a circle, many of your problems would disappear. The two-building construction of The Line, where it formed as the circle, would have a radius of just 3.3km and only 2.9km between people, rather than the incredible 57km of the currently proposed line. The circle would have issues of its own with light and ventilation. But it would make the fundamental engineering issues of urban transport disappear.

The problem with that is that the Saudi government has committed to its linear concept. Changing it now, with all the investment upheaval that entails, could in fact bring about the death of the whole project, leading the next mega-city builder to build a giant tech-enabled donut. But doing nothing to deliver The Line or its initial and rapidly shrinking promise, with aspirations truncated, investment floundering, and news reports surfacing that Saudi Arabia had authorized the use of lethal force to evict people from their homes along the proposed route of The Line, the fundamental future of The Line is more than questionable. It begins to look more like a 21st-century folly than a new city concept.

For now, the jury’s still out on The Line. Which reality wins out? The one of the city or the failed Red Sea vanity project? Keep your eyes on The Line.